Strategy and Tactics are not mutually exclusive things

“adaptable CEOs spent significantly more of their time — as much as 50% — thinking about the long term.” — HBR, ‘What Sets Successful CEOs Apart’

Did you know that the top-performing CEOs in Fortune 500 companies spend significantly more time thinking strategically and long-term?

Part of this is a by-product of running larger companies successfully. As the company size grows, you need to elevate yourself out of the weeds and towards a more long-term view.

But another part is the importance of balancing short-term, tactical work with long-term strategic intent.

Although the best-performing CEOs spend more time thinking long-term, this was still balanced against other time horizons.

Very few CEOs spent more than half their time thinking long-term; the highest performing were those who still had a healthy balance between long, mid and short-term perspectives.

Most CEOs know they have to divide their attention among short-, medium-, and long-term perspectives, but the adaptable CEOs spent significantly more of their time — as much as 50% — thinking about the long term. Other executives, by contrast, devoted an average of 30% of their time to long-term thinking.

If unbalanced, you often see a high-level strategy but nothing connecting it to the day-to-day work.

Too high-level, and organisations end up with a gap between strategic intent and day-to-day execution.

Strategy is, therefore not a single horizon — it’s not what you would classify as ‘long-term’ — but rather it‘s a continuum of long, mid and short-term.

The constant debate of ‘Strategy vs Tactics’, ‘Planning vs Execution’, and ‘Vision vs Tasks’ leaves us often behaving as though they are mutually exclusive when they’re not.

The constant debate of ‘Strategy vs Tactics’, ‘Planning vs Execution’, ‘Vision vs Tasks’ leaves us often behaving as though they are mutually exclusive when they’re not.

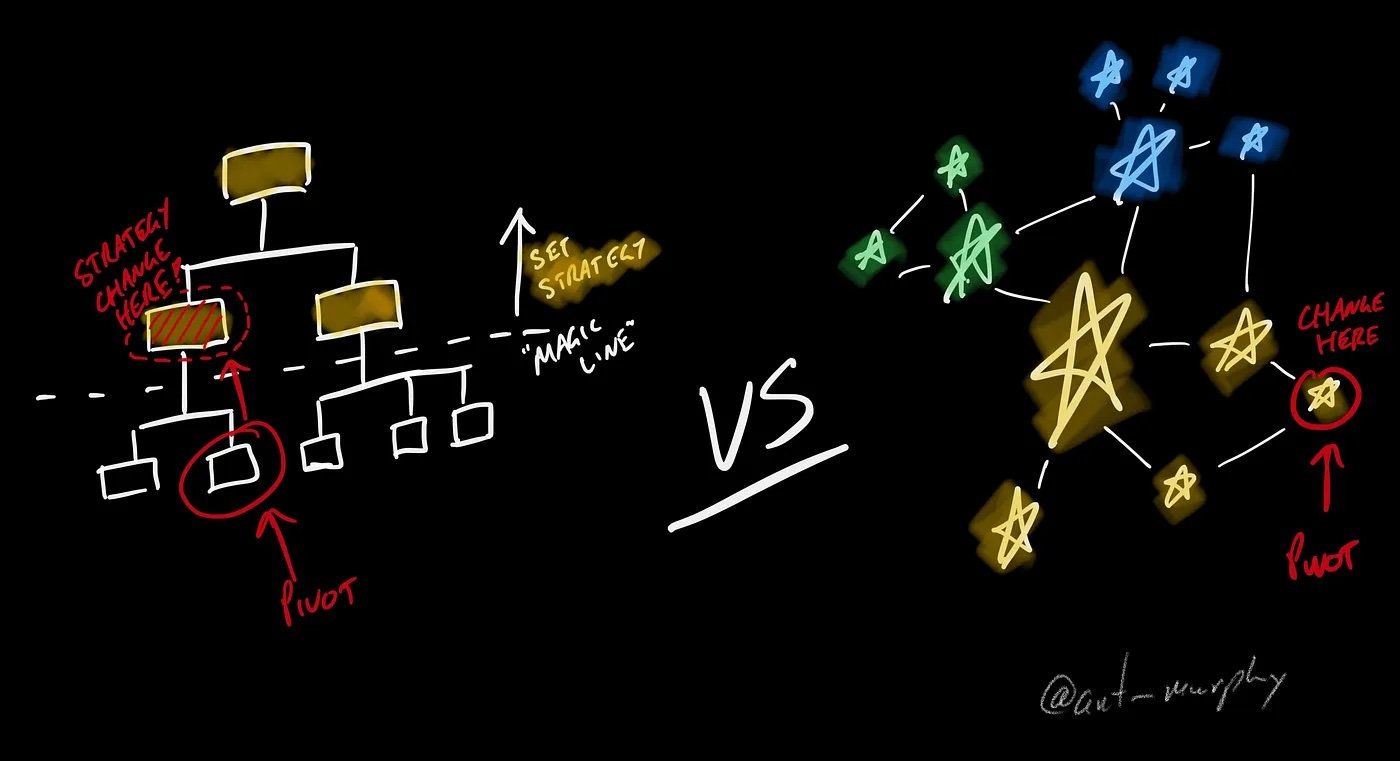

I see this often when it comes to organisational structure. The notion that there is some invisible line in the org chart where above it strategy magically happens.

The dangers of separating ‘strategy’ and ‘execution’ in your org chart — makes it much harder to pivot.

Developing a strategy without considering tactics would be like choosing your next holiday destination without any consideration for how you might get there.

Some might argue, “that’s fine…that’s empowerment and leadership… to provide the destination and not prescribe the how.”

Which is fine until you discover you don’t have a valid passport or budget to secure a visa.

“Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat.” — Sun Tzu

Without the tactical, strategies lose their most important power — connecting day-to-day work to a longer-term objective/vision — and as a result, companies end up with a gap between strategic intent and day-to-day execution.

Strategy as a 2-Dimensional Plan

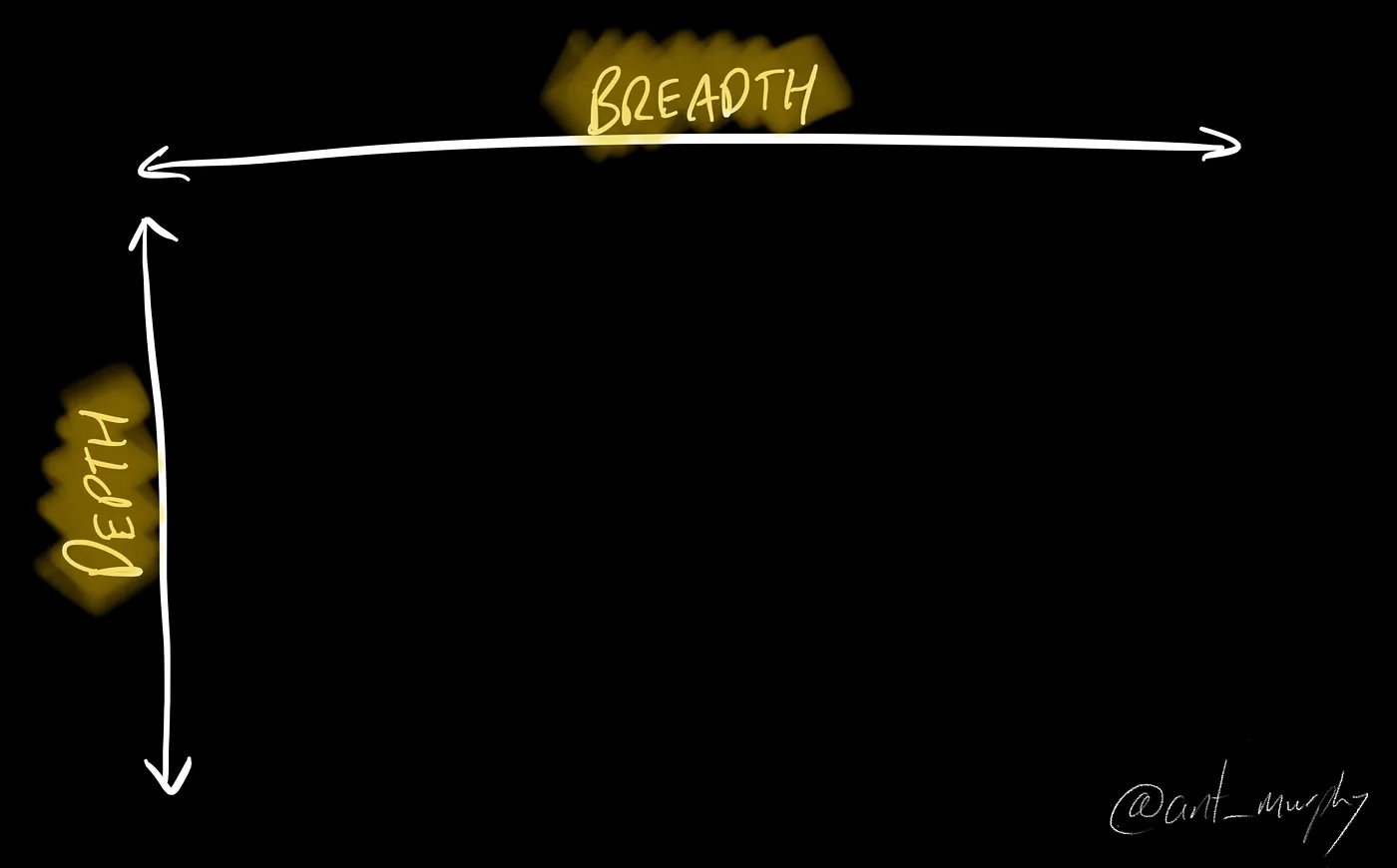

Instead I like to view strategy as a two-dimensional plane or a 2x2 matrix, as you will.

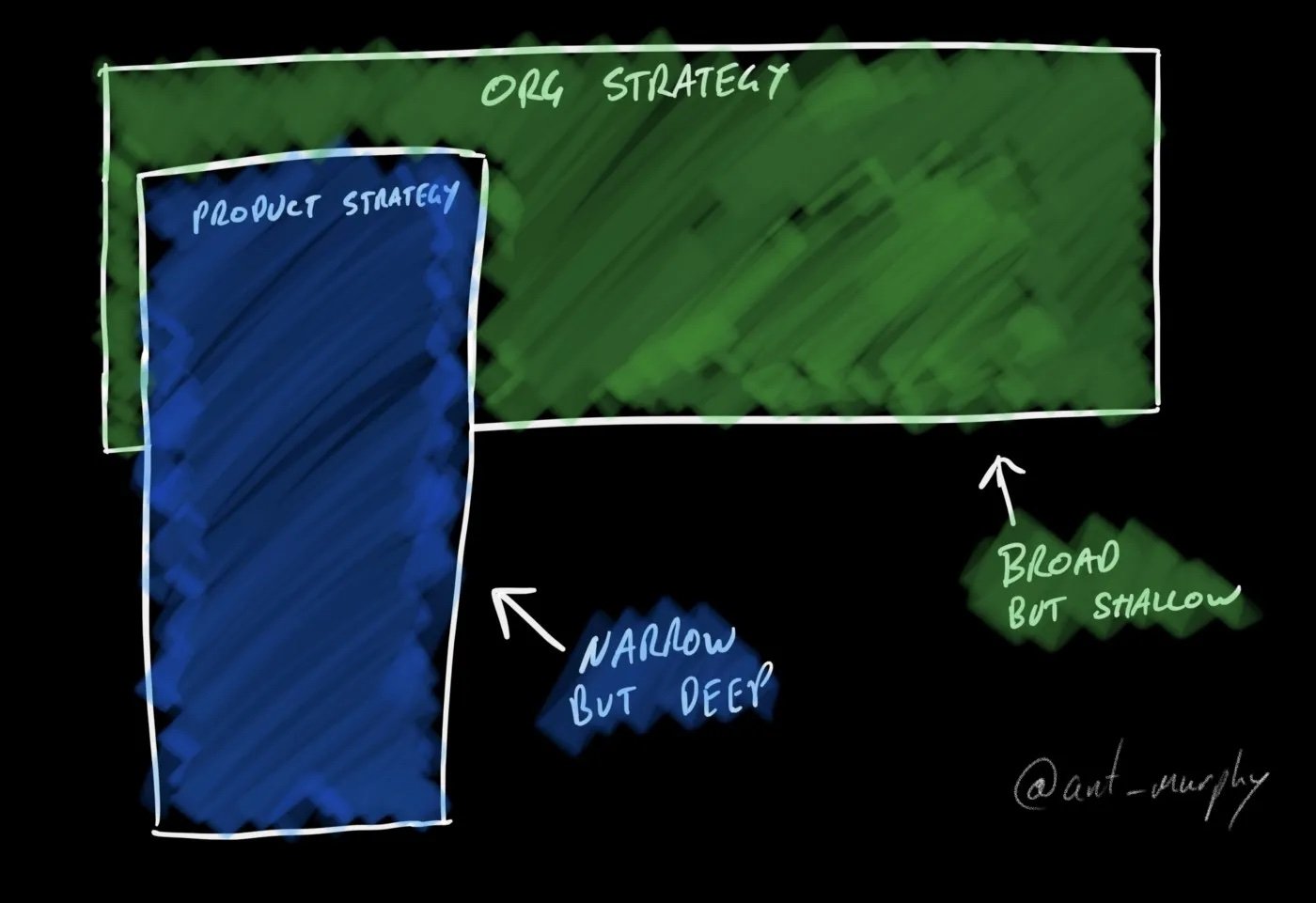

I view strategy as a two-dimensional place of breadth vs depth.

On one axis, you have what I call ‘breadth’.

Breadth is about how broad your strategy is.

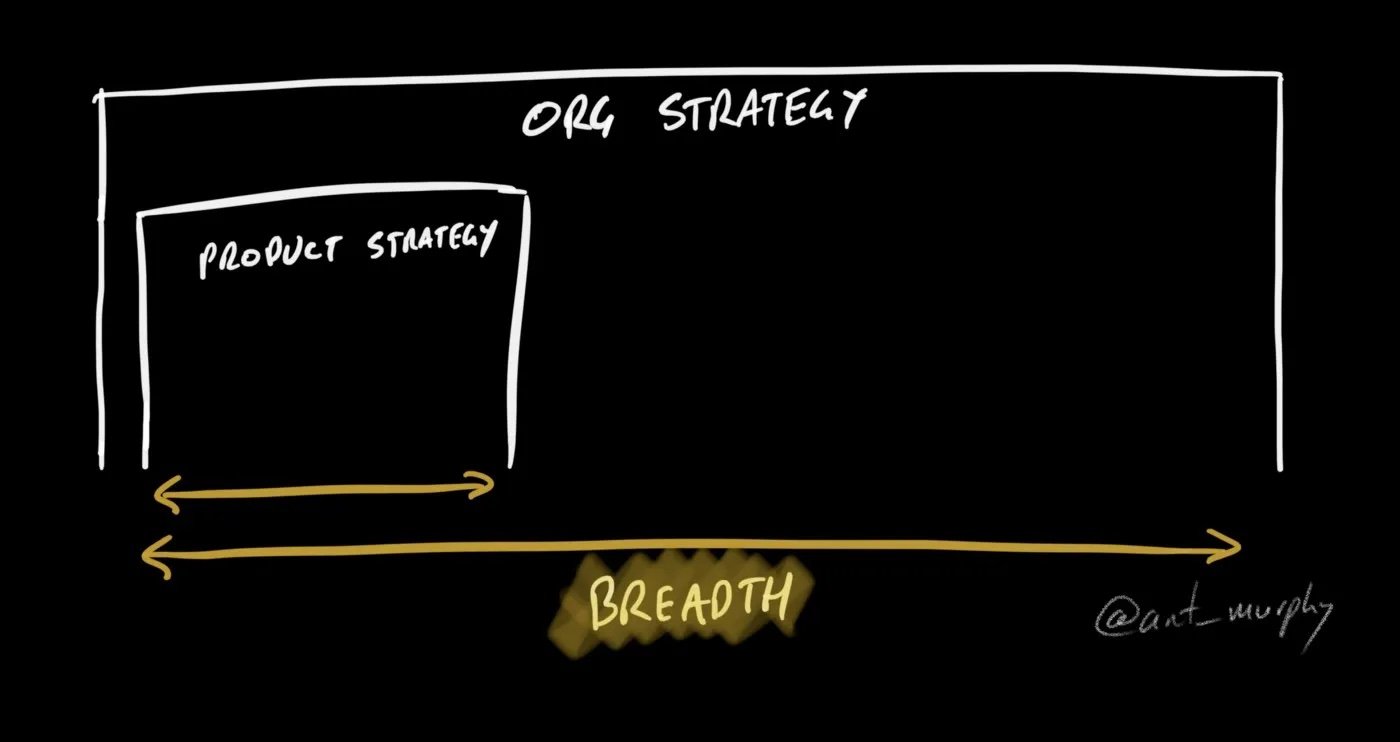

This breadth comes in two aspects. The first is a scoping aspect. For example, setting a strategy for a company is broader than setting the strategy for a product. Similarly, a company strategy would be narrower than setting the strategy for an entire country.

The second aspect of breadth is how far outside of that scope do you consider.

For example, do you consider the impacts to other aspects of the business or even externally to the industry, market, etc — how will sales use this, marketing, etc ?— how will we scale? Move to adjacent markets in the future?

Breath = how wide or narrow is your strategy? e.g. a company strategy is broader than a product strategy.

The other axis is what I refer to as ‘depth’.

Depth is about whether you consider things from both a high level and low level — i.e. do you only consider the 10,000 ft view, or do you have a high attention to detail at the same time?

Some people are brilliant at thinking big and bold but come undone by the small details.

Equally, the opposite is also true.

Others get stuck in those weeds and find it hard to consider the bigger picture.

You need both.

It’s the ability to think big while challenging yourself on the finer details.

This doesn’t mean you’re dictating or micro-managing. It’s about finding the right balance. There will be times when you will want to zoom right in, and other times when you may want to keep it zoomed out. Part of the skill of building effective strategies is finding the right fidelity.

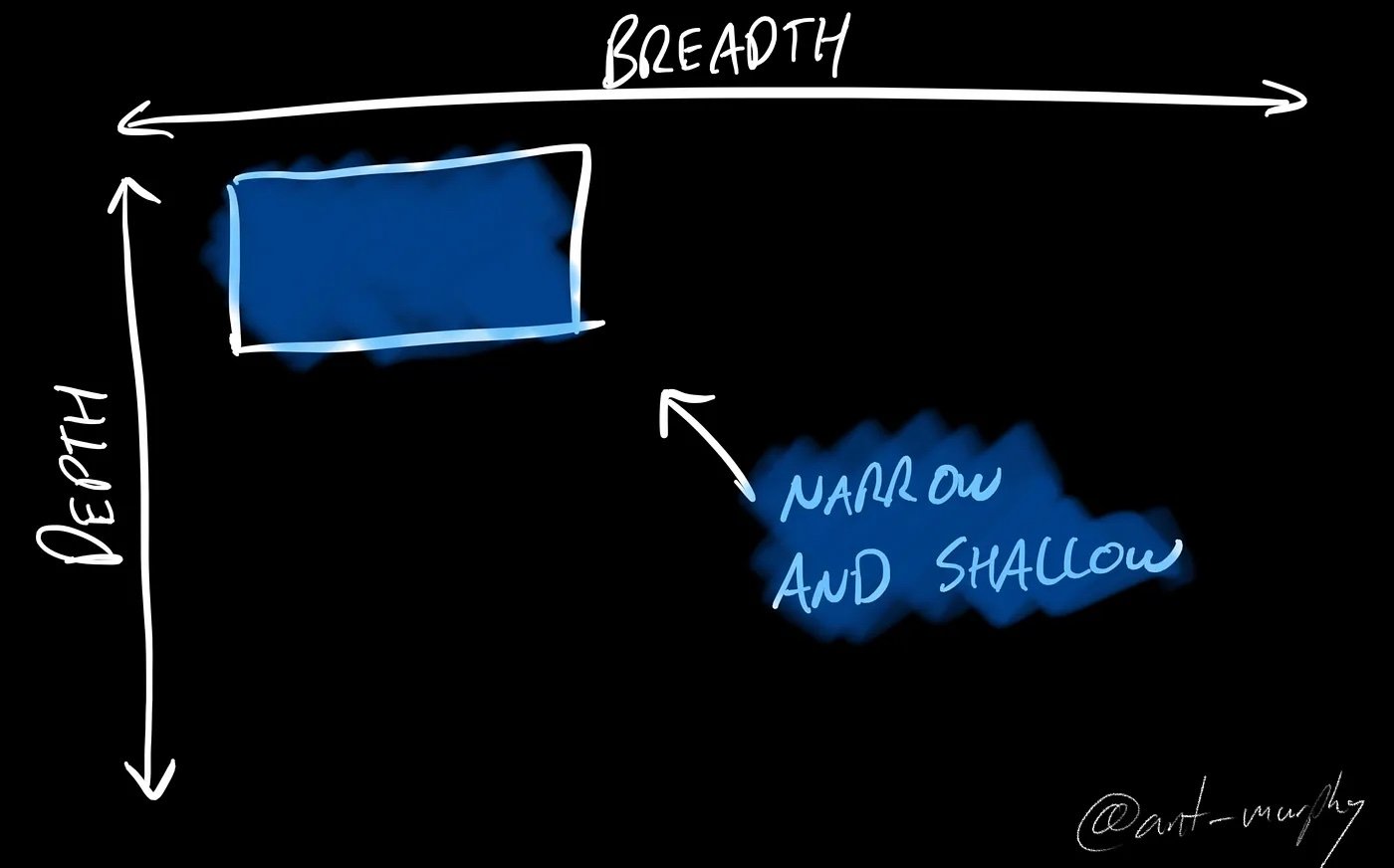

Narrow and Shallow Strategy

Narrow-and-shallow strategies are the worse kind. They are not too dissimilar to the broad-and-shallow, but they lack the breadth of consideration.

Instead, they lack the wide considerations that broad strategies have and as a result, are full of fluff.

Narrow-and-shallow strategies are the ones that look like someone wrote it down on a napkin whilst trying to rush out the door.

The lack of thought, consideration and any substance resemblance makes them the worst strategy. Or as Richard Rumelt put it in his book Good Strategy Bad Strategy: “bad strategy is the active avoidance of the hard work of crafting a good strategy.”

Visualisation of a Narrow and Shallow strategy

An example of a narrow vs broad strategy would be a high-level product strategy. One that might state something like:

“Be the best in class mobile app”

“Be the #1 provider in the country”

“Provide the optimal expericence for…”

None of these strategies truly describe ‘how’ they intend to achieve it. Nor do they describe the ‘why’.

Why do we care about being best in class what does that mean? What does it mean for the business, customer, employees? How are we going to achieve it.

“If you fail to identify and analyze the obstacles, you don’t have a strategy. Instead, you have either a stretch goal, a budget, or a list of things you wish would happen.”

― Richard Rumelt, Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters

Often narrow-and-shallow strategies are more akin to a vision or goal. Another common myth about strategy.

If your strategy doesn’t help you say no to things or make a clear prioritisation decision, then it’s too shallow and fluffy.

A good strategy should tell you not just what but how it will be achieved. It should clearly state what you are and are not choosing to do. Shallow strategies often lack this level of necessary detail. Remaining too high-level and fluffy to be actionable.

“A good strategy has coherence, coordinating actions, policies, and resources so as to accomplish an important end. Many organizations, most of the time, don’t have this. Instead, they have multiple goals and initiatives that symbolize progress, but no coherent approach to accomplishing that progress other than “spend more and try harder.” ― Richard P. Rumelt, Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters

Narrow but Deep Strategy

Narrow-but-deep strategies, on the other hand, are highly focused and detailed ones.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with a narrow-but-deep strategy. However, their detail can often give a false sense of confidence. Due to their narrow nature, external factors often blindsided narrow-but-deep strategies. Without investing the time to go broad and consider a wider range of influences, narrow strategies regularly come undone by external events.

This doesn’t mean they will always fail — strategy is a continuous process. As long as you continually review your strategy and make changes when necessary, you can pivot and adjust your narrow strategy.

However, you should expect that strategy to change frequently.

Without considering the broader impacts, things like the business strategy, market, competitor or even political influences, narrow-but-deep strategies are often blindsided by external factors and therefore are ones that constantly change.

Hallmarks of a narrow-but-deep strategy are being too internally focused. They talk a lot about what the product, department, etc are going to do in-depth but have little purview over external factors like market conditions, changes, competitors, etc.

And when they do consider external factors, it’s often limited — for example, only considering what 1 or 2 key competitors are doing.

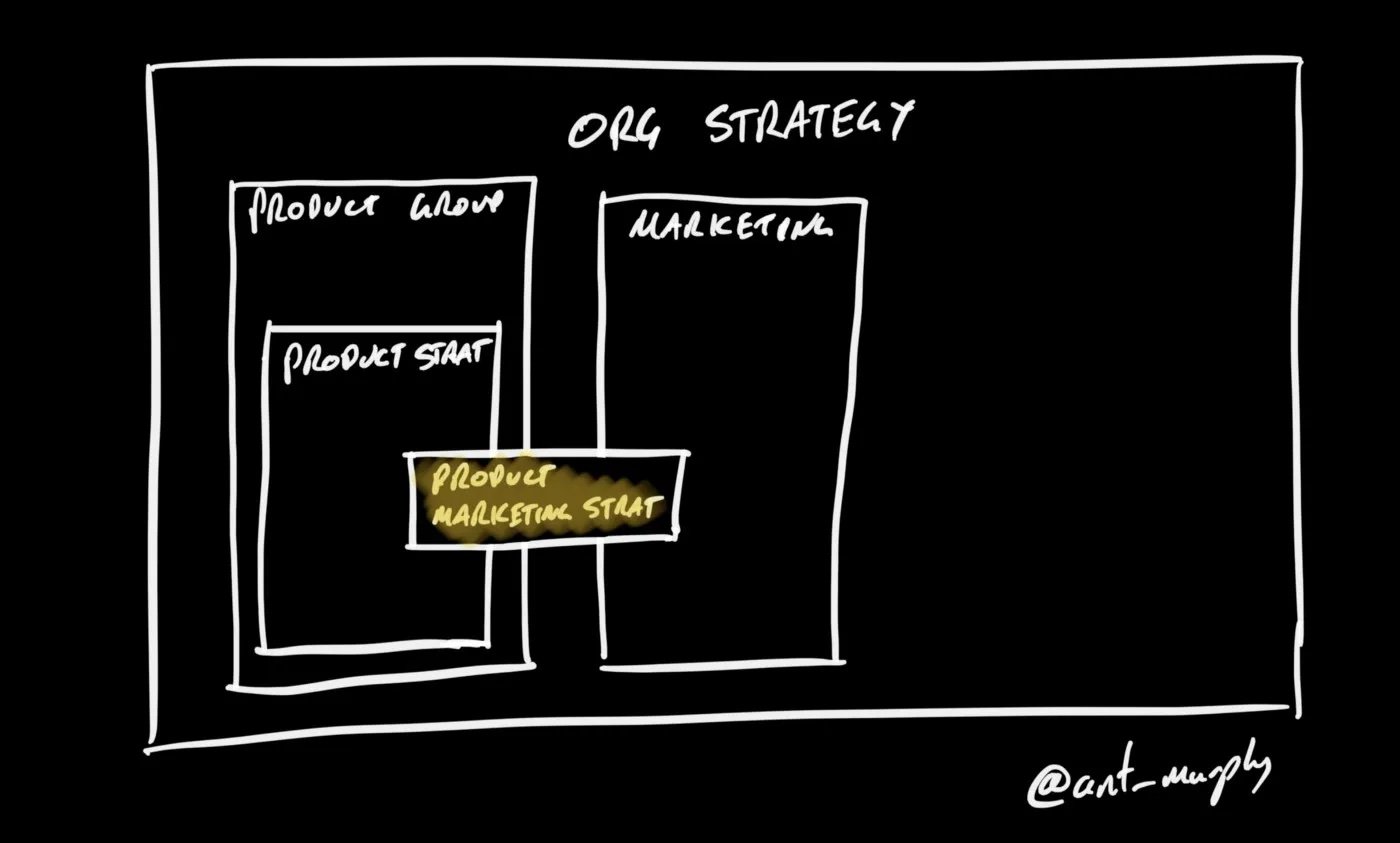

Narrow strategies also often lack cohesion with other strategies in the business — think of a product strategy without considering the company strategy.

Narrow but Deep strategy vs a Broad but Shallow.

Broad and Shallow Strategy

Broad-and-shallow strategies can seem like a bad recipe but not always.

Broad-and-shallow strategies are, as you would correctly guess, strategies that are high-level but have considered a wide range of aspects.

An example of a broad-and-shallow strategy would be a company strategy that doesn’t go into depth on the ‘how’ too much.

Board-and-shallow strategies are the most effective in larger organisations that wish to create the space for agency and autonomy.

Why larger organisations? Because in smaller organisations, there is often still a need for depth. Because you’re small, you operate on a narrower plane than larger enterprises which often have multiple business units, departments and product lines. Equally, as a large company with multiple business units and product lines, creating a detailed strategy is often difficult and unnecessary. Instead keeping things to just enough detail to provide direction and clarity whilst keeping things high-level enough to allow each business head to craft their own strategy can be the right balance for your organisation.

This can be a tricky balance to get correct — not too high level but not too detailed — perhaps it should be called the goldilocks strategy!

The blindspot for broad-but-shallow strategies are that they can easily become too high-level — too fluffy. When this happens, they become too disconnected from the day-to-day work and capabilities within the organisation to be effective.

“If you can’t identify a set of Capabilities and Management Systems that you currently have, or can reasonably build, to make the Where to Play and How to Win choice come to fruition, it is a fantasy, not a strategy.” — Roger L Martin

This will cause your strategy to be misinterpreted, leading teams down the wrong path and causing misalignment.

Too shallow and your strategy becomes meaningless.

Broad and Deep Strategy

Broad-and-deep strategies are well-considered, detailed and informed by data and research. They can be immensely powerful when done to the right level for the context.

They consider a wide range of possibilities, influences and inputs. The strategy then described in depth how these influences have led to a set of choices — both choices to do something and to not do something. As well as how these choices will be executed.

“A good strategy includes a set of coherent actions. They are not “implementation” details; they are the punch in the strategy. A strategy that fails to define a variety of plausible and feasible immediate actions is missing a critical component.” ― Richard Rumelt, Good Strategy Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters

This often results in a coherent strategy. One that people can understand the necessary context on how and why that strategy has come about. This crucial context helps teams to better understand the ‘what’ and ‘why’ they are doing something and allows for greater coherence across other strategies in the organisation.

Conclusion

Although we should strive for a broad-and-deep strategy, there’s room to consider how your company culture influences here.

If your company doesn’t value deep thought and well-articulated decisions, then a deep-detailed strategy might not be best suited. However, understand the blindspots that a shallow strategy can have.

Equally, your organisation might favour a mix of broad-and-shallow strategies at the higher echelons but narrow-and-deep ones at the lower levels.

Again consider how these two strategies can complement each other to ensure that they have each other’s blindspots covered.

Finally, it’s worth recognising that strategies will have natural ‘ebbs and flow’ to them. One moment a more deep and detailed strategy might be necessary, whereas at other times, a more shallow strategy might be better suited to allow for greater flexibility.

Multiple strategies at varying levels of breadth and depth. Coherent with each other.