How product companies operate without BAs, Scrum Masters, Release Managers, etc

This post explores why you don’t see roles like BAs, Scrum Masters, Release Managers, etc in product-tech companies - and why traditional enterprises need them.Hey Ant here, I started this newsletter to share the lessons I wish someone had told me 10+ years ago early in my product career. Expect to find practical lessons on building products, business and leadership. If you prefer podcasts or videos, check out my YouTube.

Recent posts you might have missed:

- Product mistakes I won't repeat in 2026

- How Product is Changing in 2026

- The Hardest Part of Product Management is NOT Features, it's People.

A quick favour before we get into today's post:

I’d love your help 🙏

If you know anyone who might be interested in either:

Live cohort based Product Strategy Course

Or the Product Mentorship

There’s currently 🎁$100 off the Product Mentorship until the 1st of Feb. Use code: MENTOR2026 (includes the product strategy course and ALL other courses)

I’d really appreciate a shoutout and sharing it with your team or anyone you know.

Thanks!

Firstly, what I'm about to describe might sound like an imaginary world for some of you. But it's not.

These companies exist. I've worked in them, had them as clients, and seen them operate firsthand.

I've also been where you might be today. In a large 100-year-old enterprise that still thinks it's the 1980s, doing waterfall.

I've experienced it all.

Which puts me in a privileged position to answer questions like the one I got the other day:

"I don't understand how product orgs operate without BAs (Business Analysts), Project Managers, Release Managers, Change Managers, etc?"

So I thought I'd unpack why some companies have so many different roles (BAs, QAs, Delivery Managers, Change Managers, Release Managers, other-people-with-manager-in-their-title) while others seem to get away with just product managers, designers, and engineers.

Product Managers don’t ‘feed engineering’

In traditional enterprises, product's role is often viewed as "feeding engineering."

We need to keep the engineers busy, right?

A lot of this thinking comes from waterfall and more traditional ideologies where we had "thinkers" and "doers"; aka someone who decides what to do (product managers) and those who execute on it (engineering).

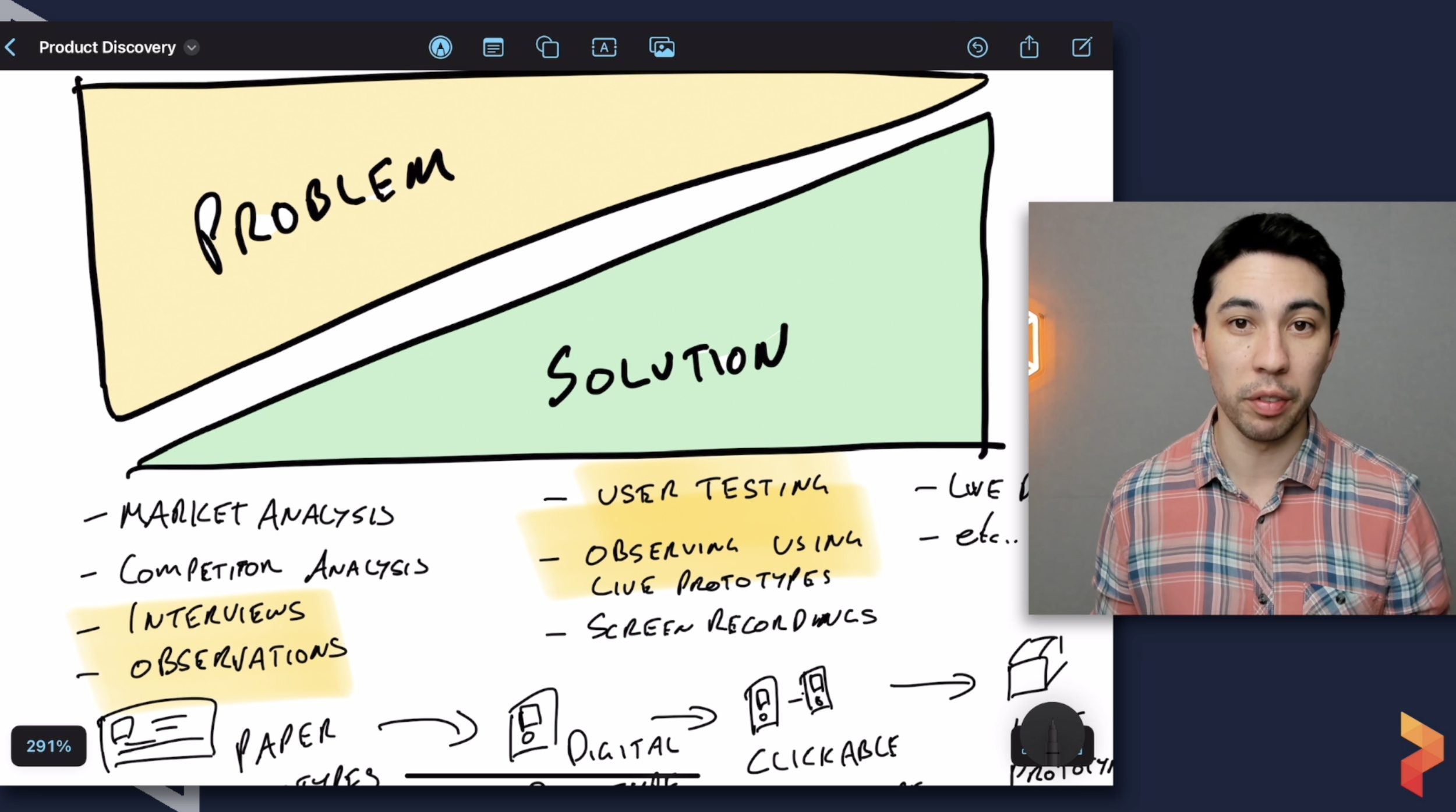

Product companies have a very different philosophy; product teams are treated as problem-solving teams, not delivery teams.

Product, design, and engineering collaborate together to define the work.

This changes two key things:

They don't need an army of BAs to write tickets to "feed the engineers"

Frees up product managers time to work on discovery and other things since it's no longer only their responsibility to define everything the team is doing.

Note: That's not to say there aren't top-down decisions in product companies. There absolutely are.

Engineers write their own 'tickets'

Some of you might be thinking: "But writing tickets means time away from coding."

And that's true. But it's only a problem if you're optimizing for output, not outcomes.

If your goal is to achieve outcomes, then time away from coding is worth it if it means spending more time discovering the right problems to solve.

This might be a surprise to some of you but in some organizations I've worked in, product managers don't even log into Jira! Instead they work largely in tools like Notion or Confluence, documenting discovery results and defining the work at a "product spec" level.

However, in other organizations product is stuck in Jira (or similar tool). They’re really a backlog manager more than a product manager and it's no wonder they don't have any time for product discovery.

Note: A key thing that makes this possible is involving engineering in discovery so they have context. The irony is that many organizations see this as slowing the team down, when in fact it can actually speed things up.

Engineering leaders take the load for delivery

In traditional enterprises, delivery management is a dedicated role - ie Delivery or Project Managers.

And again, if you’re optimizing for maximum lines of code produced, this makes sense - let’s have someone else do this so we’re not taking engineers away from coding.

But in many product organizations, delivery is viewed as the responsibility of those doing the work.

If you’re building the product, doing the tasks, then you should be the one managing that.

As a result, delivery management isn’t a separate role, it largely sits with engineering.

Which makes sense if you think about it this way:

Who would be in the best position to…

Understand the problems and challenges?

Identify dependencies (and resolve them)?

Give estimates and be accountable to them?

make smart decisions because they have the necessary knowledge and experience?

Those doing the work are.

There's more trust from stakeholders

A massive time sink for Product Managers is communication.

Whilst it’s a core part of the role, some organizations don't make communicating easy.

Two dynamics that make communication much harder in traditional enterprises:

Volume: The sheer number of stakeholders to keep informed

Demand: High communication demand, often as a result of low trust

This puts an increased overhead on the product role. Another space where time, energy and effort is going to which could be spent elsewhere. And the less time you have, the more you need to delegate and have other roles help.

They have fewer dependencies

One pattern I've observed in large enterprises: they tend to solve problems by assigning a role to it.

For example:

Releasing software is hard? Hire a Release Manager!

Delivery feels slow and difficult? Get a Delivery Manager!

The problem is this is often a band-aid solution. It doesn't fix the root cause.

Dependencies are the perfect example.

Large enterprises love to add coordination roles to help manage dependencies.

But another lens would be: Why do we have so many dependencies in the first place? And how might we reduce them?

What if we eliminated dependencies rather than tried to manage them?

Of course, at a certain scale, eliminating dependencies is impossible, but reducing the burden would still help.

I know leadership teams at some product organizations look at dependency data regularly and actively make decisions to reduce dependencies.

This could be adding roles, reshaping the teams or even changing the tech stack. But their goal is to minimize this coordination overhead.

Less coordination and there’s less of a need for coordination-type roles like Project Managers and Delivery Managers.

Higher cohesion

You might be starting to notice a theme: more overhead = more roles.

Another form of overhead is cohesion - or more accurately, lack thereof.

The best way I can describe this is dealing with competing priorities.

When things aren't aligned, and there are competing goals and conflicting priorities, it creates overhead in the form of cognitive load.

Because you’re always trying to decipher everything - perhaps some of you feel this way. Constantly doing mental gymnastics and attending alignment meetings.

All this sucks up time and effort. Time in other organizations where cohesion is high is spent on other things.

Decoupled deploy, releases and launches

I’ve written about this one before so I won’t go deep here. But the tl;dr is that product companies tend to decouple how they deploy, release, and launch their products.

You might use different terms, but here's how I define them:

Deploy = making software available on a target environment. This could be production, but it might not be.

Release = where you make newly deployed changes available to your users.

Launch = a strategic (non-technical) activity where you inform the market about specific features and changes.

When you have two or more of these connected together, you create dependencies and management overhead.

Worse, you risk a bad deployment ruining your multi-million-dollar launch event… not good.

However, when you decouple these. New features can be deployed into production at any time, often behind a feature flag. They can then be turned on for users when it makes sense (even as an incremental rollout or prior to a launch event).

There’s many benefits from working this way - not just reducing overhead.

But all this reduces the release and change burden that many traditional enterprises have.

If I can deploy in really small batches, there's not a lot to manage. This makes it easy to identify problems and fix problems.

Same with releasing to users.

When companies operate this way the change overhead is not comparable to those who do big bang releases.

Note: acknowledging there are other dimensions like regulation and risk too. I agree it makes it harder, as well as aligning with hardware and other aspects (e.g. vendors) that introduce constraints to working this way.

Teams think big but work small

Another way the change burden gets decreased in product organizations is they "think big but work small."

This means when they do go to release something, that thing is often small. It's not a 12-month initiative bundled with a dozen other things as part of an enterprise release.

Again, I get why some companies need Release, Change and Project Managers. There’s a lot of work to manage a large enterprise release. But another way to think about it is, are these big releases necessary? Because they’re expensive, painful and often full of problems.

They avoid the optimisation problem

The optimization problem is the problem of finding the best solution from all feasible solutions.

You might have experienced this before:

Person A raises that they have a problem and they're going to try X.

Person B sees similarities with what another team is doing. They're excited by the opportunity to optimize. Person B sets up a meeting to consolidate approaches and decide on a consistent approach across the org.

Person A and B both meet, perhaps several times. They map out all the possibilities, differences in context, edge cases… In the end, they spend hours seeking an approach that suits both their contexts and future needs.

After several meetings and countless hours, they finally come up with a consolidated approach.

But as the adage goes: "If you build something for everyone, it works for no one."

This is a common scenario many organizations regularly find themselves in. They spend weeks, even months, trying to find a "one-size-fits-all" solution.

This is when the optimization problem becomes a trap.

I've observed that some organizations are more susceptible to this trap than others. Some avoid it by being okay with some inconsistency and divergence, so long as they can catch it later.

Others consistently dig themselves into a hole, trying to over-optimize everything for everyone and every edge case.

This not only slows things down, but it puts a larger burden on product teams. There are suddenly 15 meetings and 20 people to consult every time you want to do something.

Again, it's no surprise that you see so many BAs (and other roles) in organizations like this. I get it. This is taxing, and there are only so many hours in the day.

Increased organizational clarity

I honestly think clarity is one of the highest-leverage things you can create as a leader in a company. I also believe it's one of the hardest, and as a result, one of the most ignored.

Because as Stephanie Leue so brilliant framed “Clarity scales better than process”

This also links back to the earlier point about cohesion.

A lack of cohesion creates cognitive load because you're always doing mental gymnastics to decipher what's going on.

The same for a lack of clarity.

When you're unclear about things, you're always second-guessing.

A simple example: "Is this problem within my remit or not?"

A lot of time and mental energy can go into answering that question.

Now compare that to an organization where there's a lot of clarity. It's clear whether it is or isn't (and if it's not, it's clear what to do about it).

This means there’s a lot more action. A lot more agency.

And as David Marquet demonstrated in his book Turn the Ship Around, it’s a pre-requisite for empowerment.

Parting Thought

A common theme across all of these is ‘cognitive load’.

The more burden and cognitive load you put on a team, the more people you need to manage everything.

Great leaders see their job as making their team’s life easier, not their own.

They actively monitor this and reduce cognitive load.

So for those leaders (and future leaders) reading this, I leave you with this reflection:

What are you currently doing to reduce cognitive load for your team?

Because we can either play product on hard mode and continue doing mental gymnastics all day long, or we can find ways to reduce the burden.

Final notes:

Please don't interpret this as product companies being perfect in any way. Everywhere has its challenges. I've seen enough companies to know the ‘grass is never greener’.

The goal of this post was to give you exposure. To hopefully describe the differences and why, when there's less cognitive load, it can be possible for engineering to lead delivery and get involved in discovery, for example.

Hope that was helpful.

I posted about this on Linkedin and it got a lot of attention so it was a data point to turn it into a newsletter post.

As always if you have any questions or if you want to work with me to audit and find ways to reduce the cognitive load, reply to this email or join the Product Mentorship.

A friendly reminder for anyone interested that there’s $100 off the Product Mentorship. Use code: MENTOR2026

The Product Mentorship includes all courses, including the NEW ‘Product Strategy in Practice’ course that was just announced.

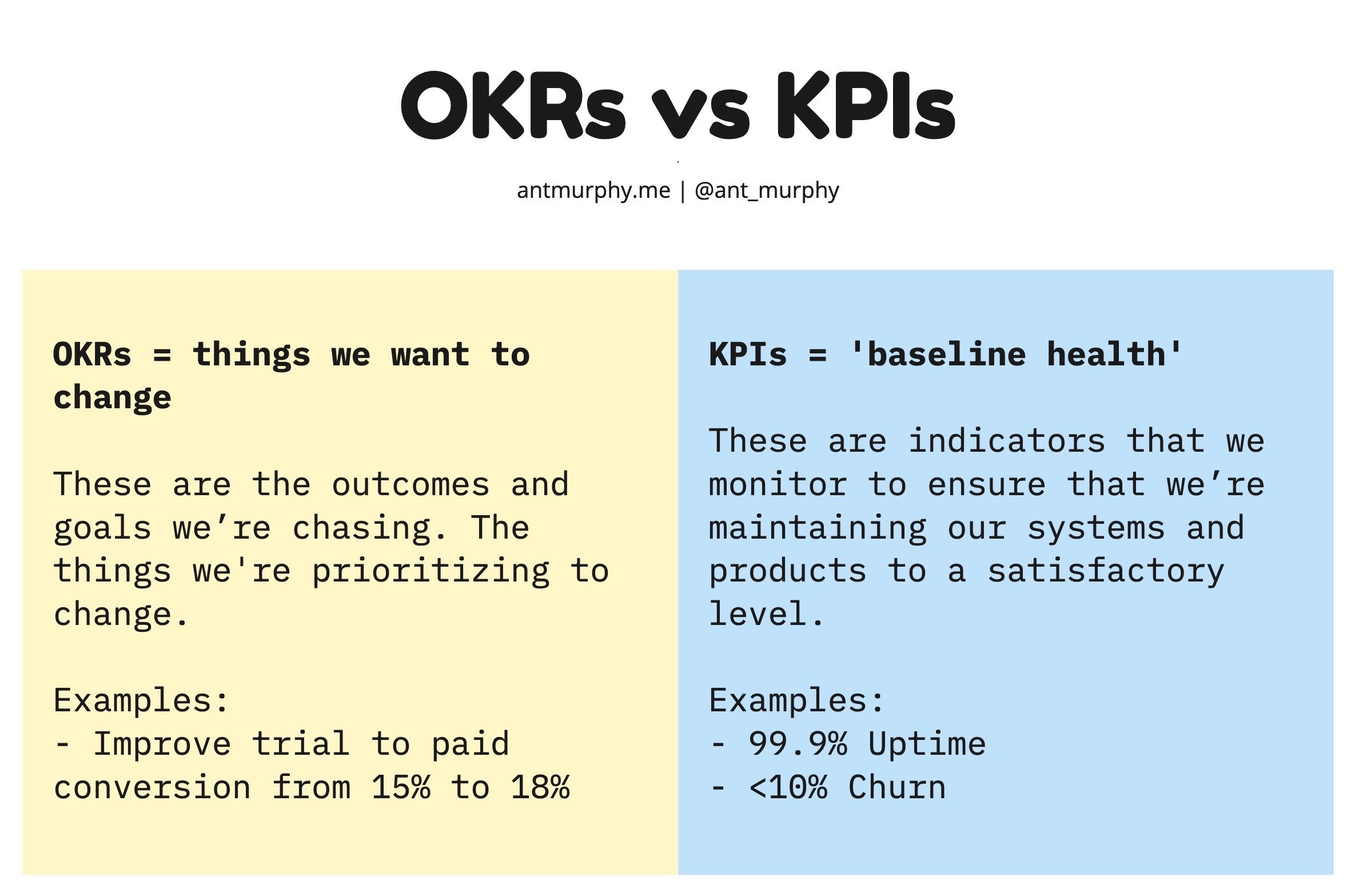

Your OKRs don’t live in a vacuum.

Yet this is exactly how I see many organizations treat their OKRs.

They jump on the bandwagon and create OKRs void of any context.

Here’s what I see all the time…